Building better language data for humanitarian responses

[This is an informal write up of a project I've been working on with UCL and Translators Without Borders. The language data products generated are in the process of being uploaded to HDX by the TWB account, and are linked individually further below.]

Disaster occurs, and a humanitarian agency jumps into action. Supplies are procured, staff are mobilized, appeals issued. In-country, the staff gather in the meeting room set aside for the response, the walls covered in maps and whiteboards. What language do the affected population speak? Arabic, right?

24 hours later, the agency’s trucks arrive at their destination, and start distributing supplies and information to the affected people. And the people speak…Arabic, which is a relief. Well, 95% of them do. The other 5% speak a mix of Kurdish and other local languages. As the operation continues, better data on language will be collected and the agency can adjust their approach - but at this initial stage the problem remains.

Good quality language data in a format really suitable for these purposes is rare. Perhaps one of the maps stuck to the wall of the response room will be a print out of a linguistic map, drawn from an academic journal, or pulled from Wikipedia. Typically these divide the country into large blocks showing only main languages, which doesn’t particularly help.

There are some paid options, like Ethnologue, who seem to have this part of the commercial language mapping sector pretty locked up. But their data, while definitely drawing on solid research and more detailed than most, also divides maps into fairly simple blocks of language, so at best it will go on the wall with the others.

To respond to this need and gap, I have been working on a partnership between University College London and Translators Without Borders to begin to address this issue. A pilot project, they wanted to know if it was possible to generate language data products that could help inform responses in these initial stages, before more detailed data collection that begins when the response is up and running.

User-focused design

The humanitarian sector is getting increasingly smart about the use and sharing of data, something we wanted to make sure we took advantage of. To ensure this, we took a user-focused approach to our design process, consulting with technical experts on both language and humanitarian data, and with humanitarian actors who were ultimately the target of our work.

These consultations imparted three important features, all of which made our products streamline with existing humanitarian workflows and language data conventions.

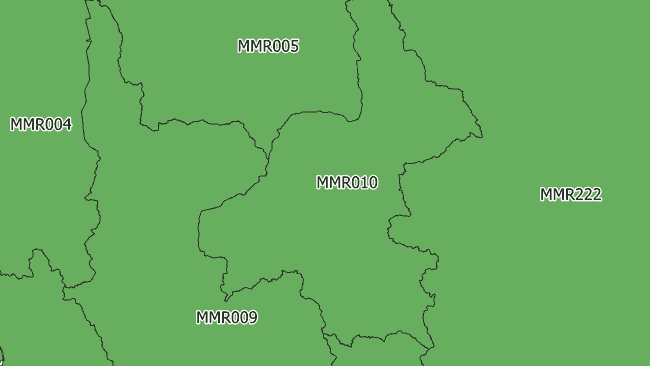

P-codes

P-codes are unique codes that refer to locations and areas on maps. They are generally maintained by UNOCHA, but sometimes are farmed out to other coordinating or info management actors in countries. The Humanitarian Data Exchange has administrative area data with P-codes available for most pertinent countries. They’re used extensively in the development and humanitarian sector and are incredibly useful for joining data and quickly producing thematic maps. While the name of areas may change between languages, the P-code remains the same.

To ensure that our data could be easily incorporated into existing humanitarian workflows, we decided to use these standard administrative areas with P-codes as the structure of our data. For each district, province, and country, we would provide population language data that could be easily joined to existing data, or added to workflows making use of P-codes.

These admin area and P-code datasets don’t exist for every country – only those that have experienced sufficient humanitarian focus. Luckily they did exist for every country we focused on at this pilot stage, though some were rather out of date which caused some complications for matching data. One day I would love to have the ear of OCHA’s leadership team and try to convince them to centralise P-code administration, rather than create it reactively on a needs basis.

Humanitarian Exchange Language (HXL)

HXL is a more recent innovation in humanitarian data, and a really exciting development. A HXL tag is added to a column of data below the header, before the data starts. These tags provide a standard description of the data in the column, dramatically increasing interoperability and making it uniformly machine readable.

For example, if we had a column noting the percentage of population living in urban areas, we could call it ‘%_urban_pop’, ‘pop_urban_perc’, ‘percent_urban_population’, or any number of combinations and shorthand. The HXL tag for this, made up of a single hashtag and two qualifying attributes, would always be #population+urban+pct.

Pre-existing HXL hashtags did not exist for some of our data categories: this kind of work, where language itself is treated as an indicator of sorts, is less well trodden ground in the sector. As such we worked with the HXL team to make sure our custom HXL tags were logical and consistent with the wider HXL standard.

ISO 639-3 codes

One of a family of five ISO 639 code systems used to refer to languages, we chose to use the 639-3 variant, which boasts the broadest list of languages. These three letter codes provide a descriptor of the language in question, such as ‘eng’ for English, and ‘cmn’ for Mandarin Chinese. Besides being machine readable, these codes are useful in instances when languages may be spelt differently, or where working with data in a foreign language.

Besides these, this iterative design process informed the format and the design of our metadata. Data products are provided in tabbed Excel files, individual CSV files for each administrative level, with a PDF of the metadata. A rating of our confidence is provided for each individual line of data, and notes in the metadata provide some account of how this was determined.

Wrangling the data

This being a pilot project, we began with countries where some existing language sources were readily identifiable. The ideal data here is good quality census data, which in some lucky cases was already relatively well packaged for conversion to our format. In several cases the full census data was not available, but usable census microdata could be accessed from IPUMS International. For our purposes the microdata was placed in a database and subject to SQL queries to extract the information we required. Of course not all censuses are themselves up to standard, and we tried to reflect this in our data confidence notes.

Sometimes only ethnic data was available. In the case of Uganda, where language is closely tied to ethnicity, this might be suitable for conversion to language data with the help of academic sources on ethnic language use. We are still reviewing both the validity of this process and our concerns over mapping ethnicity (discussed in a later section), so data for Uganda has not yet been finalised.

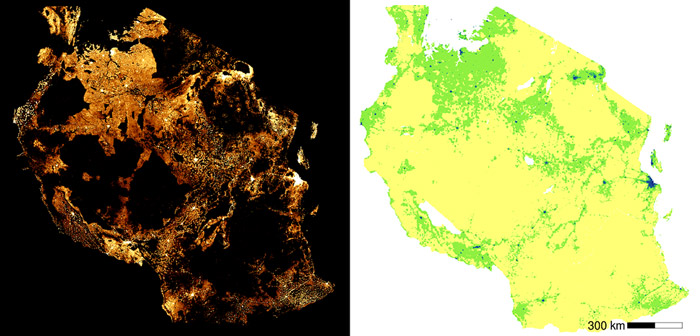

Myanmar provided an opportunity to do a bit of the creative GIS work that I always enjoy. The Myanmar Information Management Unit has a map of language areas that we digitised in order to overlay with our administrative areas – but to add greater accuracy we added a WorldPop population density raster to the workflow. This meant if, for example, an area was split between Chin and Burmese, but the Chin areas had a high population density, Chin would be allocated a greater % language share.

Hopefully soon Facebook will release one of its new high resolution population maps for Myanmar, which would increase accuracy over the Worldpop raster. That said, even with this improvement, the Myanmar map would be considerably less accurate than those drawn from good quality census data.

Some countries were incredibly challenging. Good language data was available for Ukraine, but matching census area names to those of the OCHA administrative was a challenging process. Another challenge was that languages were sometimes repeated in the data under a different name, or a dialect of another language might have been collected separately in the original data. These had to be checked and matched in a largely manual process. Here DRC and its 242 languages temporarily defeated us, and the current file still likely contains some repeated languages. These will be revised in future versions.

Tools, now and in future

Some tools were built over the course of the pilot, which I’ll try to tidy up and share on my GitHub. In some cases we had access to language data at a smaller administrative levels, but not the larger levels, like provinces or regions. In this case the language shares for the larger units had to be calculated based on the shares and population of the smaller units within them. For this situation I built a tool in R to automate this process. This code could easily be adapted for use in any comparable scenario, not just with language data.

Our language data for Uganda was collected prior to wide reaching changes to the size and shape of administrative areas. As such, I worked on a tool that took the language data for the older areas and reattributed it to the newer areas, based on percentage shares of overlap. While this tool worked, it was best suited to datasets with limited numbers of languages in a simple geographical arrangement. For example, if a district spoke one language in its west, and another in its east, both would be partially allocated to a new district that intruded just in its western extremity. As such it risks adding considerable noise and inaccuracy to the data. It would be interesting to apply population density data to the process, though the underlying problems would persist.

We also made use of html parsing, using the BeautifulSoup Python package, in order to systematically scrape data and associated text. In future, we would like to build a collection of interesting tools for directly gathering data – such as natural language processing. There is really interesting work going on here, and tools like Facebooks's fastText library are very good at detecting the language of written text.

Data ethics and protection issues

Working with this kind of data means we also need to consider ethical questions (the Centre for Humanitarian Data has some good guidance here), and for each individual dataset we worked through these risks with experts. A couple of interesting issues stuck out:

Language as a proxy for ethnic mapping

Needless to say, in many countries the ethnic arrangement of the population is a controversial topic. It’s for this reason that we were unable to procure language data for much of the Middle East – censuses in places like Iraq have avoided collecting ethnic data to avoid stirring up controversy over demographic data.

Generally, we felt that since our data was all aggregated to administrative areas, it could not realistically be used to target ethnic populations to a degree not already available to any bad actor interested in doing so. That said, in part due to an unwillingness to come anywhere close to that danger, we have not provided data at much smaller Admin 3 levels, even where available. In some cases we did not feel ready to release country data until the risks and context are better understood.

Under-reported ethnic minority languages

Foremost here was the Rohingya language in Myanmar, whose language shares were very small. As described above, Myanmar’s data was drawn from a digitised language map overlaid with population density data, and some limitation in that data has led to an underreporting of Rohingya speakers. Other ethnic languages do not seem to have been under-reported to the same degree.

That said, these figures may actually now be accurate, since so many Rohingya speakers have now fled the violence in northern Rakhine. However other minority languages may also be under-reported, and no supporting data or specialist knowledge is available for verification. Since shares under 0.1% are not shown, many of these languages would not appear at the Admin 0 (country) level in our data. In order to avoid presenting data for Myanmar which unduly omits minority languages and potentially provides grist for the political mill, we have not provided admin 0 level data.

The finished product

At this stage in the project, we have data ready for 9 countries: DRC, Guatemala, Malawi, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, The Philippines, Ukraine, and Zambia (I'll add links here as TWB uploads them to HDX). These have been placed on the Humanitarian Data Exchange. We also produced some static and interactive web-based maps, which will be hosted on TWB’s website.

Do they completely answer the question of what language an agency should prepare their materials in? Not completely. To provide the definitive answer to that we would need perfect data on not just people’s main language or mother tongue, but their use of lingua francas, and possibly also the mutual intelligibility of dialects. We’ll keep working on that. But at the very least, agencies can now get a sense of the diversity of language, rather than assume that Arabic alone will do.

Looking to the future

What’s next for the project? We’ll work on more countries, better data and more tools. Our DRC data needs work to ensure that languages and their dialects aren’t repeated, and the data itself could do with verification. We’re also going to try to tackle another intimidatingly complex country: Nigeria, with an incredible 520 languages.

We’ll also eagerly listen for feedback on the data and its format, and continue to ensure that the products are as operationally viable as possible.

And some thanks

Thanks to all those experts and allies who fed into the design of both project and product, particularly the HXL team who put up with a lot of very finickity questions.

For other projects, return to the main page.